Red Gold

Red Gold

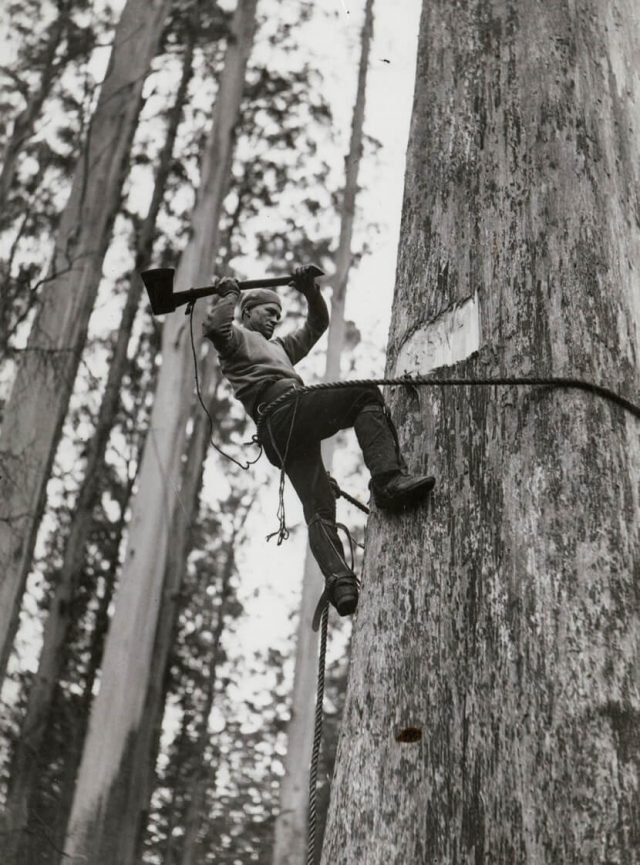

High in the canopy of a towering red cedar, William Mazlin steadied himself on a springboard wedged into the trunk, the rich red bark rough against his palm. Around him, the Australian rainforest stretched in every direction. The air was thick with moisture and the earthy scent of decomposing leaves, while a soft drizzle misted through the canopy above.

Somewhere in the understorey, a whipbird cracked its sharp call, and the forest floor far below was carpeted with ferns and fallen logs slowly returning to soil. Among the shadows, insects buzzed and clicked, while lizards darted between leaves and fungi, each creature with a part to play. William adjusted his grip on the crosscut saw and glanced down at his partner, who was driving wooden wedges into their carefully planned cut. They had pegged a ladder into the side of the tree the day before, climbing high enough to fell it above the flare of the butt, where the timber was cleaner.

The plan was simple: bore in from both sides, guide the fall with ropes, and get clear when the giant began its thunderous descent. But there was nothing simple about bringing down a tree that had stood for centuries, its trunk big enough to house a family, its top disappearing into the mist above. A misjudged angle, a shift in the wind, and the tree could twist or splinter as it came down.

Somewhere nearby, a bush stone-curlew let out its eerie, wavering cry, half-cry, half-keening wail, and a whipbird answered in a sharp crack followed by a falling note, like a whip drawn across the air. The scent of fresh-cut wood already hung in the air from their morning's work, that distinctive, almost sweet aroma of red cedar that would soon grace the drawing rooms of Brisbane, Sydney and London.

William took one last glance at the wedge-shaped notch below and wiped his hand on his shirt. Then he set his feet, lifted the axe, and began the cut.

The Last of the Giants

By the 1880s, when William and his brothers reached North Queensland from Sydney, red cedar had earned its nickname of "red gold" for good reason. The timber's magnificent deep red colour, combined with its resistance to termites and ease of working, made it the most sought-after wood in the colony. But the Mazlin brothers had travelled north because the easily accessible cedar of New South Wales was largely exhausted.

Trees that had taken centuries to grow were felled in less than an hour, their logs floated down rivers and creeks to sawmills and shipped to furniture makers in the growing Australian cities. Within decades, these forest giants would be commercially extinct, leaving only their remnants in antique furniture. This story unfolds without considering the Aboriginal people who had lived among these trees for thousands of years, whose displacement paralleled their destruction.

Mixed Inheritance

Learning that my great-great-grandfather William Mazlin (1856-1941) had worked these forests filled me with mixed emotions. There was undeniable pride in his courage and skill, in his willingness to climb sixty-metre giants with nothing but an axe, rope and raw determination. William was one of four brothers who travelled north from Sydney, sons of Thomas Mazlin (1819-1894), whose own father had been a convict transported to Botany Bay in the early 1800s and later became a timber-getter. These young men helped establish the towns of Evelyn, Herberton and Atherton, contributing to a growing colony that promised opportunity, land and wealth.

Yet that initial excitement gave way to harder questions.

What did it mean that a creek in North Queensland still bears our family name? Mazlin Creek threads through what was once pristine rainforest. These waterways became arteries for floating timber to the coast, and their names now mark not just our family's presence, but our participation in something irreversible.

If you have traced your own family's colonial history, you may recognise these mixed feelings. That strange combination of admiration for ancestors who showed such determination, yet unease about what their success required. The knowledge that the places we visit on family holidays, the towns where our relatives first prospered, were built on choices we might struggle to make today.

The Pattern Repeats

My family's story isn't unique. In the Amazon, fourth-generation ranchers defend cattle stations carved from rainforest. Indonesian palm oil farmers work on plantations established by their forebears, who cleared ancient forests. In Canada, logging families with century-old ties to the timber industry watch old-growth forests disappear. All face the same impossible choice between survival and preservation.

William and men like him were not villains. They were ordinary people making rational decisions within the systems of their time. Yet their individual choices, multiplied across thousands of settlers, created consequences that stretch far beyond their original intentions.

What stories lie untold in your family history? Have you uncovered ancestors whose choices both built and destroyed the world you inherited? I'd love to hear about the complex legacies you've discovered. You are most welcome to share your story in the comments below.